Swan Creek: Bringing back salmon in an urbanized watershed

Ian Browning

Summary

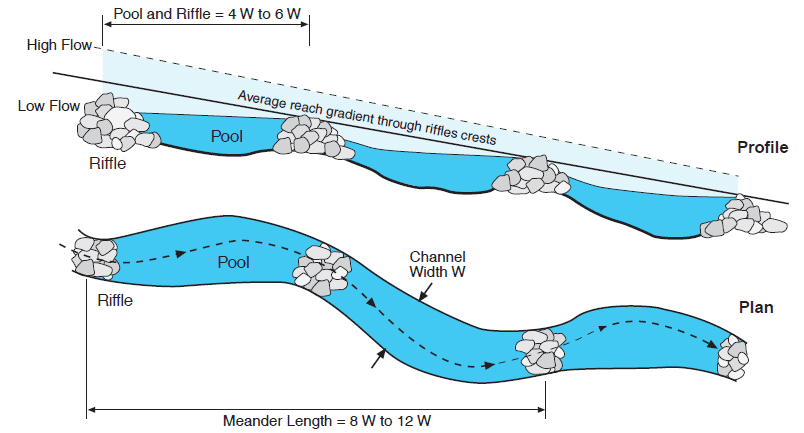

Swan Creek, in the Greater Victoria municipality of Saanich, runs 2.3km from Swan Lake to the Colquitz River. Over the past 150 years the area surrounding the creek has transitioned from a natural wetland area influenced by the presence of beaver and indigenous peoples, to agricultural land, and more recently to a highly urbanized watershed. This transition from natural to agricultural to urban has caused degradation of the creek encapsulated by the term urban stream syndrome. Key factors include high levels of impervious surface in the watershed, high pollutant and nutrient inputs and a modified stream channel. Despite these challenges the creek has demonstrated the potential to once again become fish bearing. Looking to the future, restoration efforts have begun and are ongoing to bring the creek back to a functional ecosystem that will support salmon and a range of native wildlife. Restoration activities include rebuilding pool-riffle channel structures, providing gravel spawning sites, increasing fish/wildlife habitat for various life stages, and improving riparian habitat. While the creek will not return to its full wild condition, with careful restoration design and improvements in storm water infrastructure in the watershed, it should be possible for the creek to support a range a native fauna and flora and become both a cherished community asset and significant ecological corridor. |

Genealogy

|

Swan Creek located on the Saanich peninsula of Vancouver Island is a small urban creek that flows from the outlet of Swan Lake to the larger Colquitz River and on to the ocean through the Gorge waterway. Swan Lake that feeds the creek was formed in a glacial depression some 11,700 years ago (Swan Lake n.d.), and as the glaciers retreated the land revealed below would have been re-colonized by plants, animals and indigenous peoples migrating into the newly revealed land. In geological terms this is a relatively young landscape. The vegetation would probably have developed over the following centuries to be similar to the small patches of old-growth forest that still stand today and are characteristic of the Coastal Douglas Fir, moist maritime (CDFmm) biogeoclimatic region. Before European colonization of the island beginning around 150 years ago (Fort Victoria was established in 1843) (Horne, 2012), the landscape around the creek would have been influenced by

|

both indigenous peoples, whose known history in the region stretches back around 4000 years (Saanich Archives n.d.), and the animal life that occupied the area. North American beaver (Castor canadensis) were an important driver behind the fur trade that attracted early settlers and being ecological engineers they would likely have been a major influence on the hydrology of the whole region altering the path of streams and creating pools, wetlands and flood plains. Salmon (Oncorhychus spp.) would also have been abundant in the region, as they are today and as reported by indigenous elders and early settlers. The plant and animal communities would also have been influenced by indigenous peoples through hunting, fishing and cultivation of various plants (notably Camas – Camassia quamash) by frequent low-intensity burning (Turner and Hebda, 2012). Much of the peninsula would probably have been a mix of Garry Oak meadows, Douglas Fir forest and wetlands with many smaller streams and creeks than the present day.

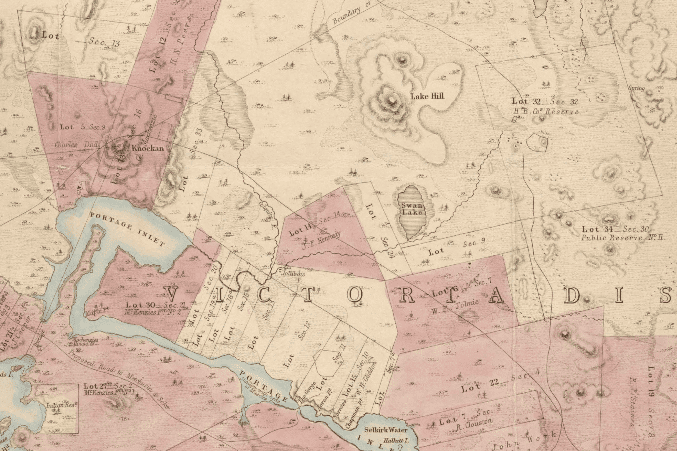

The peninsula was ‘purchased’ from the first-nations occupants in the 1850s for 386 wool blankets (CRD n.d.), and with the arrival of the European settlers the rate of land use change around the creek accelerated. An early map (1858) of the area is shown in figure 1 below.

The peninsula was ‘purchased’ from the first-nations occupants in the 1850s for 386 wool blankets (CRD n.d.), and with the arrival of the European settlers the rate of land use change around the creek accelerated. An early map (1858) of the area is shown in figure 1 below.

|

Land records show the allocation of land parcels beginning in the 1860s (Saanich Archives n.d.) and clearing of the Douglas Fir and Garry Oak forests and drainage of wetlands for agriculture would likely have followed, as well as the extirpation of beaver and larger mammals/predators over time. These activities would have had a major influence on the whole Colquitz watershed of which Swan Lake and Swan Creek are a part (Swan Creek is a sub-watershed of the larger Colquitz). These changes are illustrated by an air photograph from 1926 (figure 2) showing the extent of the clearing (National Air-photo Archive) and another 1964 air-photo, figure 3, (Provincial Air-photo Warehouse) showing the extent of urban development over that time. Another photograph (figure 4) taken from mount Tolmie in 1930 (Saanich Archives) shows how the region would have looked in general around that time as land was cleared of trees and wetlands drained to make way for agriculture.

|

|

An early resident of the area recalls that the area surrounding the lake was “spongy” to walk on and that some neighbors harvested peat to burn (Castle, 1989), indicating that the area around the creek was a probably a wetland/bog for a considerable period before colonization.

The change from likely mixed forest/wetland to agricultural use would have had a major impact on the creek as rates of sediment and nutrient load increased and farmers may have modified the stream path and riparian vegetation to make way for crops. Grazing animals would also likely have negatively influenced the creek as it was common agricultural practice to allow cattle and other livestock access to the creek for water. Swan Lake itself was used as a dumping ground for raw sewage, a dairy farm, and a winery, but cleanup of the site began in the 1970s (Swan Lake n.d.). Early houses in the vicinity date from the 1920s with the housing density increasing steadily from that time with consequent increase in road densities and impervious surface area increased along with pollutant loads (from vehicles, industry and domestic sources) discharged into the creek from a developing storm water system. A recent conversation with a long-time resident of one of the suburban areas surrounding the creek reveals that 30 years ago the creek was a “mass of blackberries” and that the municipality had performed various bank-stabilizations using rip-rap. Since that time the Creek has been cleared in some sections which are now municipal park, although some reaches are still quite inaccessible. Restoration of the creek began in 2012 (Peninsula Streams n.d.) with the formation of the Friends of Swan Creek group and is currently ongoing. |

Socio-ecological characterization

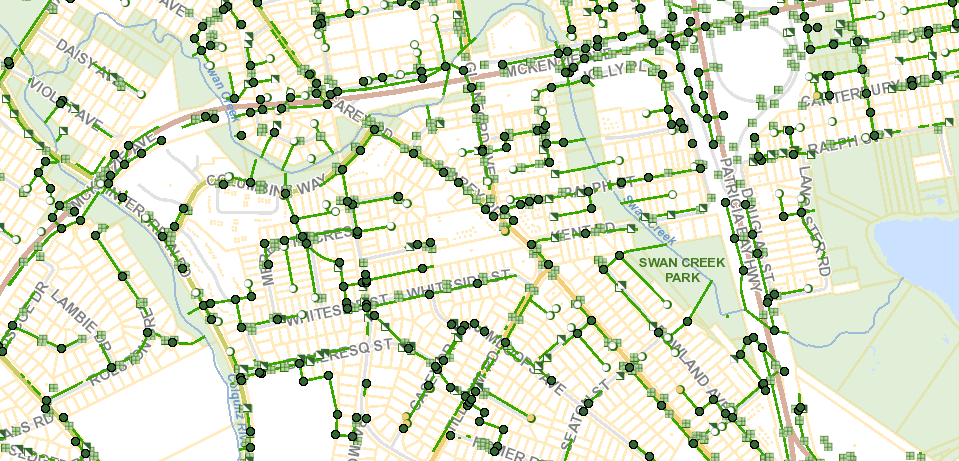

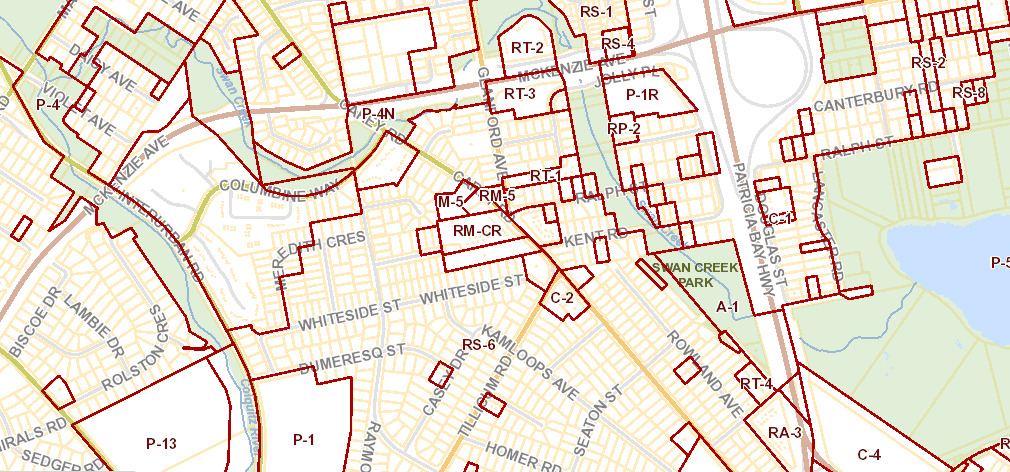

The 2.3km long Swan Creek (CRD), after many decades of development in the surrounding area, is now predominantly an urban stream experiencing many problems common to urbanized streams/creeks known collectively as the urban stream syndrome (Walsh et al. 2005). Although land development around the creek is relatively dense, the creek does have some riparian buffer zone in the form of Swan Lake Nature Sanctuary, municipal/park and private land adjacent to the creek as shown in figure 5 below (Townsend, 2010).

Management of the creek is governed by multiple bodies including the Municipality of Saanich (Official Community Plan), the Capital Region District (CRD), the Swan Lake/Christmas Hill Nature Sanctuary (SLCHNS), BC Ministry of Environment/Province of BC as well as federal bodies such as the DFO (Department of Fisheries and Oceans, aka: Fisheries and Oceans Canada) and Environment Canada. Each of these bodies administers and enforces acts and regulations relating to the creek (for example: storm water, zoning, riparian regulations, water act, fisheries act etc.)

The primary impacts to the creek at present (Swan Lake, 2010) are described below:

Management of the creek is governed by multiple bodies including the Municipality of Saanich (Official Community Plan), the Capital Region District (CRD), the Swan Lake/Christmas Hill Nature Sanctuary (SLCHNS), BC Ministry of Environment/Province of BC as well as federal bodies such as the DFO (Department of Fisheries and Oceans, aka: Fisheries and Oceans Canada) and Environment Canada. Each of these bodies administers and enforces acts and regulations relating to the creek (for example: storm water, zoning, riparian regulations, water act, fisheries act etc.)

The primary impacts to the creek at present (Swan Lake, 2010) are described below:

- Flashy hydrograph. Damaging surges in flow rate during high precipitation events due to the coverage of impervious surface area (24%) of the surrounding land.

|

|

Despite these deficiencies the creek has shown the capacity to support salmon again and various restoration activities are being conducted to improve the stream and riparian habitat. |

Future trajectory

The future of Swan Creek will likely be a trajectory towards recovery of some of its previous ecological functioning as well as increasing amenity value to the surrounding community. Restoration efforts have begun to support the return of salmon to the creek, to improve its physical channel condition, and enhance the riparian areas along the creek. This effort was sparked by the observation of 60 Coho salmon seen in the creek in 2012 but with no spawning habitat available (Peninsula Streams, 2012).

Although the creek is currently degraded, urbanization, the main factor driving degradation, has stabilized to some extent and is controlled by zoning regulations. The frequent heating oil spills of the past (Times Colonist. 2013) should abate with the switch away from oil to gas/electric home heating systems encouraged by incentive schemes (Saanich Incentives, 2016) and the high cost of spill remediation borne by the homeowner.

Beneficial changes in the watershed may also help improve future conditions in the creek. Better management of storm water through the elimination of cross-connections with sewage systems and the incorporation of rain gardens may improve the hydrological conditions and quality of water entering the creek. Rain gardens (which serve as a limited surrogate to the original wetlands surrounding the creek) could be an effective means of countering the high proportion of impervious surface in the watershed, may serve to raise the water table (beneficial as Summer drought potentially intensifies), and improve surface runoff through pre-filtratio’ in soil/microbe complex (Rain gardens, 2016). A few strategically placed rain gardens at the storm water outflow points would be a significant immediate improvement to the ecological integrity of the creek. However, threats to ALR (Agricultural Land Reserve) land could be problematic in future if development and land use changes are allowed up-stream in the Blenkinsop valley (ALR, 2016).

In the past two Summers, sections of the creek have been severely dried out with no observable surface flow or standing water in some sections. A proposed weir at the outflow of Swan Lake (Bruce, I. personal. Communication. August 2016.) would serve to retain winter rainfall in Swan Lake in order to keep Summer flows at higher levels to maintain biodiversity and fish habitat. The weir would serve a similar purpose to beaver dams (Pollock et al. 2014) that would have likely existed before the land was settled. Beaver reintroduction, although beneficial in some stream restoration cases, is unlikely to occur naturally or deliberately due to concerns over flooding and potentially negative human/beaver interactions.

Although the creek is currently degraded, urbanization, the main factor driving degradation, has stabilized to some extent and is controlled by zoning regulations. The frequent heating oil spills of the past (Times Colonist. 2013) should abate with the switch away from oil to gas/electric home heating systems encouraged by incentive schemes (Saanich Incentives, 2016) and the high cost of spill remediation borne by the homeowner.

Beneficial changes in the watershed may also help improve future conditions in the creek. Better management of storm water through the elimination of cross-connections with sewage systems and the incorporation of rain gardens may improve the hydrological conditions and quality of water entering the creek. Rain gardens (which serve as a limited surrogate to the original wetlands surrounding the creek) could be an effective means of countering the high proportion of impervious surface in the watershed, may serve to raise the water table (beneficial as Summer drought potentially intensifies), and improve surface runoff through pre-filtratio’ in soil/microbe complex (Rain gardens, 2016). A few strategically placed rain gardens at the storm water outflow points would be a significant immediate improvement to the ecological integrity of the creek. However, threats to ALR (Agricultural Land Reserve) land could be problematic in future if development and land use changes are allowed up-stream in the Blenkinsop valley (ALR, 2016).

In the past two Summers, sections of the creek have been severely dried out with no observable surface flow or standing water in some sections. A proposed weir at the outflow of Swan Lake (Bruce, I. personal. Communication. August 2016.) would serve to retain winter rainfall in Swan Lake in order to keep Summer flows at higher levels to maintain biodiversity and fish habitat. The weir would serve a similar purpose to beaver dams (Pollock et al. 2014) that would have likely existed before the land was settled. Beaver reintroduction, although beneficial in some stream restoration cases, is unlikely to occur naturally or deliberately due to concerns over flooding and potentially negative human/beaver interactions.

|

The aim of all these modifications is to return the creek to proper functioning condition along its whole length such that natural processes can act to maintain the physical integrity of the creek without resorting to continual human management and repair. Figure 12 shows a partially restored section of the creek.

|

Planned restoration activities include the following:

|

Other future and ongoing restoration activities include:

- Riparian habitat enhancement: Removal/clearing of invasive species and replanting of riparian area with suitable native species to provide bank stabilization, shading to maintain cooler summer temperatures and habitat for other terrestrial native species.

- Fish (salmon) re-introduction: A number of Coho salmon fry were released into the creek by the Friends of Swan Creek under the guidance of the Peninsula Streams society in 2014. Further releases may be conducted in future depending on the return rate. Over thirty salmon were counted (per day, over two days) during the 2016 spawning season (Swan Creek Steward. Personal communication).

Although Swan Creek will not likely return to historical conditions of a few centuries ago, through restoration and stewardship activities it will regain some of its potential as fish and wildlife habitat. Clearly the future of the creek relies on an element of human design, albeit emulating natural processes, and so could be classified as a hybrid or partially designed ecosystem. The aim of the restoration is to produce a functioning self-sustaining ecosystem. However, its urban nature likely means an element of management will be required in the future so although the creek will have many novel elements and species it would not be classified as a novel ecosystem (Hobbs et al, 2014).

Regardless of how we choose to classify the creek, it will provide a valuable resource to wildlife in an urban setting and provide the surrounding community with an enhanced space to connect with and appreciate nature. The spectacle of spawning salmon in the midst of suburbia would surely be a hopeful sign of city dwellers increasingly valuing natural systems and protecting them for future generations.

Regardless of how we choose to classify the creek, it will provide a valuable resource to wildlife in an urban setting and provide the surrounding community with an enhanced space to connect with and appreciate nature. The spectacle of spawning salmon in the midst of suburbia would surely be a hopeful sign of city dwellers increasingly valuing natural systems and protecting them for future generations.

References

ALR 2016. Saanich agriculture and food security task force. SWOT analysis notes.

Castle, G. [ed.] 1989. Saanich, an illus. history. ISBN 0-9694072-0-3. Manning Press. Sidney. BC.

FHRP (Fish Habitat Rehabilitation Procedures) 1997. Watershed restoration technical circular; no. 9. Ministry of lands environment and parks. ISBN 0-7726-3320-7

Richard J Hobbs, Eric Higgs, Carol M Hall, Peter Bridgewater, F Stuart Chapin III, Erle C Ellis, John J Ewel, Lauren M Hallett, James Harris, Kristen B Hulvey, Stephen T Jackson, Patricia L Kennedy, Christoph Kueffer, Lori Lach, Trevor C Lantz, Ariel E Lugo, Joseph Mascaro, Stephen D Murphy, Cara R Nelson, Michael P Perring, David M Richardson, Timothy R Seastedt, Rachel J Standish, Brian M Starzomski, Katherine N Suding, Pedro M Tognetti, Laith Yakoband Laurie Yung. 2014. Managing the whole landscape: historical, hybrid and novel ecosystems. Front Ecol. Environ. 12(10): 557–564, doi:10.1890/130300

Horne, J. 2012 WSANEC Emerging Land or Emerging People. Arbutus Review Vol. 3, No. 2

Pollock, M. Timothy, J. Beechie, Joseph, M. Wheaton, Chrise, E. Jordan, Bouwles, N. Weber, N. and Volk, C. 2014. Using Beaver Dams to Restore Incised Stream Ecosystems. Bioscience. Vol 64. No 4.

Rain gardens. 2016. Storm water best management practices. District of Saanich.

Saanich (District of), 2009. Colquitz Watershed. Proper Functioning Condition (PFC) assessment. Aqua-tex Scientific Consulting.

Streamline. (n.d.) Restoration of riffle:pool sequences in channelized streams. BC’s stream restoration technical bulletin. Vol 2. No. 2

Townsend, L. 2009. Urban watershed health and resilience, evaluated through land use history and eco-hydrology in Swan Lake watershed (Saanich, B.C.). M.Sc Thesis

Townsend, L. 2010. Swan Lake Adaptive Ecosystem Management Plan. Retrieved from: http://www.swanlake.bc.ca/pdf/Management%20Plan%20Swan%20Lake%202010.pdf

Turner, N. & Hebda, R. 2012. Saanich ethnobotany : culturally important plants of the WSANEC people. Royal BC Museum

Walsh. et al. 2005. The urban stream syndrome: current knowledge and the search for a cure. Walsh, C. J. Roy, A. H. Feminella, J. W. Cottingham, P. D. Groffman, P. M. Morgan, R. P.

Journal of the North American Benthological Society. 24(3), 706-723. Retrieved from:

http://www.umces.edu/publication/urban-stream-syndrome-current-knowledge-and-search-cure

Web References:

CRD (Capital Region District) (n.d.). Retrieved Oct. 20th, 2016 from: https://www.crd.bc.ca/

National Air-photo Archives http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/earth-sciences/geomatics/satellite-imagery-air-photos/9265

Peninsula streams. 2012. http://peninsulastreams.ca/archives/swan-creek-restoration-and-stewardship

Peninsula streams [society]. Retrieved Sept. 12th, 2016 from: http://peninsulastreams.ca/

Saanich Archives. Retrieved Nov. 20th, 2016 from: http://www.saanich.ca/EN/main/parks-recreation-culture/archives/collections-research.html

Saanich Incentives, 2016. Retrieved Sept. 25th, 2016 from: http://www.saanich.ca/EN/main/community/sustainable-saanich/climate-change-energy/programs-rebates/home-energy-retrofit-incentives.html

Swan Lake [Nature Sanctuary] (n.d.) Retrieved Nov. 15th, 2016 from: http://www.swanlake.bc.ca/the-sanctuary.php

Times Colonist, 2013. Retrieved Nov. 08th, 2016 from: http://www.timescolonist.com/news/local/home-heating-tank-leaks-oil-into-swan-lake-sanctuary-1.64905

Note [1]: Figure 2 and 3 Air photos obtained via Townsend (2009)

Castle, G. [ed.] 1989. Saanich, an illus. history. ISBN 0-9694072-0-3. Manning Press. Sidney. BC.

FHRP (Fish Habitat Rehabilitation Procedures) 1997. Watershed restoration technical circular; no. 9. Ministry of lands environment and parks. ISBN 0-7726-3320-7

Richard J Hobbs, Eric Higgs, Carol M Hall, Peter Bridgewater, F Stuart Chapin III, Erle C Ellis, John J Ewel, Lauren M Hallett, James Harris, Kristen B Hulvey, Stephen T Jackson, Patricia L Kennedy, Christoph Kueffer, Lori Lach, Trevor C Lantz, Ariel E Lugo, Joseph Mascaro, Stephen D Murphy, Cara R Nelson, Michael P Perring, David M Richardson, Timothy R Seastedt, Rachel J Standish, Brian M Starzomski, Katherine N Suding, Pedro M Tognetti, Laith Yakoband Laurie Yung. 2014. Managing the whole landscape: historical, hybrid and novel ecosystems. Front Ecol. Environ. 12(10): 557–564, doi:10.1890/130300

Horne, J. 2012 WSANEC Emerging Land or Emerging People. Arbutus Review Vol. 3, No. 2

Pollock, M. Timothy, J. Beechie, Joseph, M. Wheaton, Chrise, E. Jordan, Bouwles, N. Weber, N. and Volk, C. 2014. Using Beaver Dams to Restore Incised Stream Ecosystems. Bioscience. Vol 64. No 4.

Rain gardens. 2016. Storm water best management practices. District of Saanich.

Saanich (District of), 2009. Colquitz Watershed. Proper Functioning Condition (PFC) assessment. Aqua-tex Scientific Consulting.

Streamline. (n.d.) Restoration of riffle:pool sequences in channelized streams. BC’s stream restoration technical bulletin. Vol 2. No. 2

Townsend, L. 2009. Urban watershed health and resilience, evaluated through land use history and eco-hydrology in Swan Lake watershed (Saanich, B.C.). M.Sc Thesis

Townsend, L. 2010. Swan Lake Adaptive Ecosystem Management Plan. Retrieved from: http://www.swanlake.bc.ca/pdf/Management%20Plan%20Swan%20Lake%202010.pdf

Turner, N. & Hebda, R. 2012. Saanich ethnobotany : culturally important plants of the WSANEC people. Royal BC Museum

Walsh. et al. 2005. The urban stream syndrome: current knowledge and the search for a cure. Walsh, C. J. Roy, A. H. Feminella, J. W. Cottingham, P. D. Groffman, P. M. Morgan, R. P.

Journal of the North American Benthological Society. 24(3), 706-723. Retrieved from:

http://www.umces.edu/publication/urban-stream-syndrome-current-knowledge-and-search-cure

Web References:

CRD (Capital Region District) (n.d.). Retrieved Oct. 20th, 2016 from: https://www.crd.bc.ca/

National Air-photo Archives http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/earth-sciences/geomatics/satellite-imagery-air-photos/9265

Peninsula streams. 2012. http://peninsulastreams.ca/archives/swan-creek-restoration-and-stewardship

Peninsula streams [society]. Retrieved Sept. 12th, 2016 from: http://peninsulastreams.ca/

Saanich Archives. Retrieved Nov. 20th, 2016 from: http://www.saanich.ca/EN/main/parks-recreation-culture/archives/collections-research.html

Saanich Incentives, 2016. Retrieved Sept. 25th, 2016 from: http://www.saanich.ca/EN/main/community/sustainable-saanich/climate-change-energy/programs-rebates/home-energy-retrofit-incentives.html

Swan Lake [Nature Sanctuary] (n.d.) Retrieved Nov. 15th, 2016 from: http://www.swanlake.bc.ca/the-sanctuary.php

Times Colonist, 2013. Retrieved Nov. 08th, 2016 from: http://www.timescolonist.com/news/local/home-heating-tank-leaks-oil-into-swan-lake-sanctuary-1.64905

Note [1]: Figure 2 and 3 Air photos obtained via Townsend (2009)